The divide between research and teaching is foreign to Anna Shternshis, the Al and Malka Green Associate Professor of Yiddish Studies and the Director of the University of Toronto’s Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies. Her research interests in a heritage project of honouring and reviving the world of Yiddish-speaking Jews in Russia and the former Soviet Union—their lives, music and culture—fused with her teaching of modern languages have created a distinct classroom for students interested in learning a less-commonly taught language.

“Contemporary scholarship on language acquisition,” as Shternshis explains, “emphasizes that learning a language is best achieved through speaking.” But how do you teach a language like Yiddish, which has its roots in multiple languages (German, Hebrew, Aramaic and Slavic), has no country affiliation, follows the written form of Hebrew, is currently practiced predominantly in Hassidic communities, and seemingly has no relevance in the 21st century?

Shternshis wanted to highlight its richness, importance, and motivate students to learn it—not as the language of a culture destroyed during the Second World War, but as a language that is alive today. Her aim is to build bridges—between her research and teaching, and between Yiddish as a practiced and living language and Yiddish as a language of the past.

In 2005, through ITCDF funding, Shternshis began the project of reviving her Yiddish language curriculum, which would reconceptualise her approach to both teaching and research. She enriched her Yiddish language course lessons through multimedia presentations, complete with the video clips, artwork, grammar rules and additional elements of language learning. She worked with an undergraduate student with a computer-science background, who previously had taken her Yiddish class. That student worked on the graphics, getting permissions for photos and organizing the material into a visually attractive, coherent structure of modules in an online course. Each module integrated visual content with media elements and practical exercises, allowing students to explore Yiddish in several modalities.

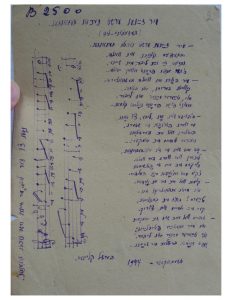

Much of the content emerged from her extensive archival research across Eastern Europe (and the world). For example, she incorporated long lost collections from the Ukrainian National Library in Kiev. It was there that she discovered Yiddish songs—both the lyrics and musical scores—written by Jews during the Second World War. Incorporating these materials into lessons allowed students to explore examples of handwritten Yiddish. Through these writing samples, students could compare written Yiddish to the Hebrew alphabet. Yet, Shternshis wanted students to experience Yiddish more fully—through listening and watching, as a living language which they could practice. To that end, she began collaborating with contemporary musicians (like Psoy Korolenko) to reconstruct the songs found in the archives. Recordings by Korolenko and other artists have been incorporated into the course curriculum so that students could fully immerse themselves into the cultural context of the language. Additionally, she reached out and made recordings of present-day Yiddish writers so that students could hear these “writers reading their own work in their words.” A stateless language of the past had been transformed into present-day reality for students.

There is no doubt that in Shternshis’ course, art and scholarship have been fused into a distinct learning experience for students. Through this approach, students’ learning moved from a focus on grammar, the traditional way of teaching Yiddish, to practice through interaction with various multimedia elements in and out of class. But this teaching approach also reframed Shternshis’ research, leading to products beyond traditional forms of scholarship such as musical pieces. It also led to the organization of a conference entitled “Technology and Language Learning”, which explored how to create an immersive experience for learning a language that lacks a country, as well as the upcoming release of an album featuring Yiddish wartime songs.

Through ITCDF funding, Shternshis reimagined Yiddish curriculum at the University of Toronto. She is also proud of how this new teaching approach, based on use of multimedia, has helped her train graduate students, many of whom will constitute the next generation of teachers of Yiddish.