Before Facebook, and before Reddit, there was BIOME—the social networking site at U of T that rivaled both at its peak.

Helmed by Corey Goldman, now the Associate Chair of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, BIOME was just a simple single-threaded discussion board for his biology students when it first went online in 1998. But after winning an ITCDF grant in 2003, Goldman was able to update it into a proper website that became an integral part of the Life Sciences student community.

“It was ahead of its time,” Goldman told me from behind the desk of his office.

But don’t just take his word for it. The office is adorned with BIOME-related distinctions, including the trophy and plaque he received for winning The Learning Partnership’s National Technology Innovation Award in 2005.

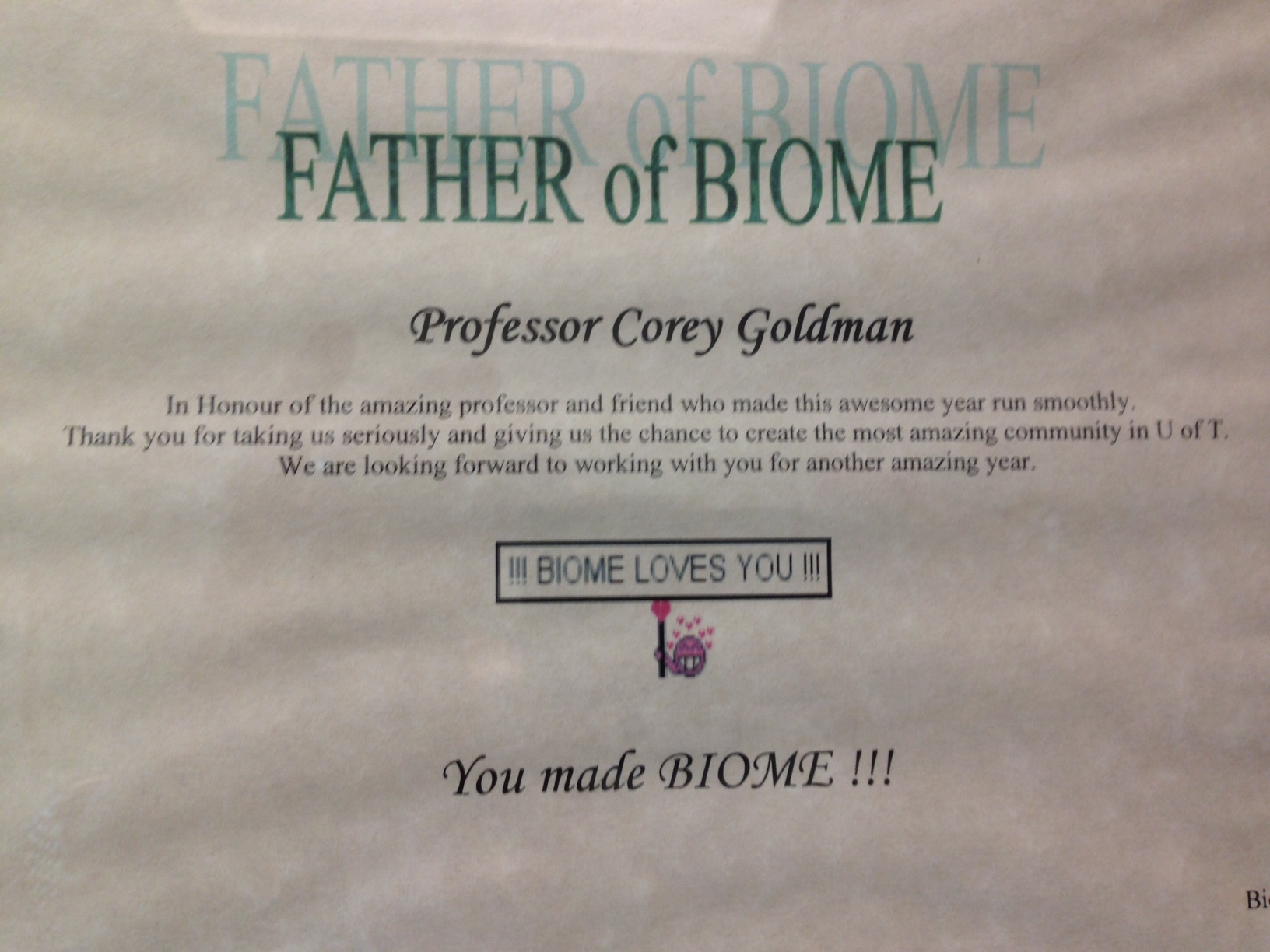

It’s the other framed plaque on his wall though, the one awarded to him by his students for being the “Father of BIOME”—the one with a smiley-face emoji surrounded by pink hearts holding up a sign that says “BIOME LOVES YOU”—which hangs most proudly. That’s because BIOME became more about the community it fostered among the students than it did the courses that everyone was theoretically supposed to be talking about.

It was the students who spurred Goldman into starting the website in the first place. This was back in the internet’s nascent stage, when the world’s most powerful corporations had websites that looked like something a 12-year-old with two hours could create today. BIOME was just a discussion board similar to most of the other early-internet boards at the time, created so that Goldman’s students could have a freer outlet for discussion than the official class board.

So the thread didn’t always stick just to what Goldman was teaching. Over time, discussions about other subjects that students had together became more and more common.

“We noticed that the students were slowly discussing not just biology,” Goldman said, “which was really cool. We realized students want to go to one place to talk about all of their courses.”

Goldman embraced this development, and by 2002, once more at the behest of his students, the discussion board had moved to a forum-style website where multiple threads could be created.

As its popularity grew, Goldman applied for the ITCDF grant, and was able to hire a developer to turn it into a full-fledged website, as well as retain a staff member who spent about half their time overseeing the website’s day-to-day functions. The chat was now separated by year of study, so students could more readily seek out their closest peers. There was now the BIOME name (as in “Biology & Me,” and also the term for a specific community of plants and animals), plus sections for coursework and other class information.

But the foundation of the website was still the forums. And it was one discussion thread in particular—the General Chat, in which students could discuss anything—that Goldman thinks defined the website.

“The General Chat was always the most popular section. Without that, there’s no way BIOME would have been as popular as what it was.”

The ability for students to discuss topics like favorite movies, sports, and hangout spots was important because it allowed them to establish relationships inside and outside of class. Many users began calling themselves “biomers,” Goldman said, and had a number of ways to identify as such.

There were mugs and lanyards created and used by the group, the latter of which Goldman still sports as a keychain to this day. There was also a BIOME softball team playing intramurals, plus biomer pub nights, bowling trips, and —“infamously,” Goldman says— the annual BIOME snowball fight in the U.C. quad.

At its peak, during the school year in 2006 and 2007, over five thousand of the six thousand or so Life Sciences students in Arts and Science were using the website in some capacity, with 220 different forums covering an amazing 120 different courses. There were usually over a thousand unique visitors per day. With so much traffic, 50 student moderators were needed to oversee things.

In fact, Goldman insists that BIOME only became successful due to student input.

“I can only take credit because the students asked. The idea is just to listen to the students. When they need resources, that’s where I come in.”

That meant that when the resources weren’t needed anymore, however, it was time for Goldman to bow out. BIOME came to an end in 2010, when Goldman realized that the time and effort he and his staff put into the website weren’t worth it anymore, in the wake of Facebook groups and other popular new websites butting into the space that BIOME was occupying.

Still, even then, his students created a U of T club in order to make their own website to keep BIOME running.

“We may have ended a year or two early,” Goldman said. “But we wanted to end on a high note.”

By the time the project was through, thousands of students had benefitted over the years from Goldman and his collaborators’ work. On a PowerPoint presentation Goldman gave when asked to speak about the project in 2007, pictures of smiling students sit above quotes so glowing they could’ve come from paid actors in an infomercial.

“BIOME is like going to an extra tutorial,” one says. “I’ve met some of the greatest people through BIOME,” says another. And yet another: “BIOME gives us a sense of friendship and community no matter where we live.”

Of course, like any scientist, Goldman gathered some numbers to back this up. At the year-end evaluation survey he gave in 2007, 85 percent of the people who used the website said it was a useful resource, and that number rose to 90 percent for first-year students.

So it would be natural to view the end of BIOME as a significant loss to the community, but Goldman doesn’t see it that way. Because really, its most important functions didn’t end, they just moved somewhere else. BIOME’s legacy lives on with another project that Goldman spearheaded: First-year Learning Communities, or FLCs (“flicks”).

“It became obvious to me from Biome that students wanted to meet each other, face-to-face, most of all,” Goldman said. So back in 2006, he created FLCs at the University of Toronto.

FLCs are groups of around 25 first-year students who take the same slate of courses together, and meet up regularly for academic and social events, overseen by advisors. Students in FLCs help each other study for all their shared courses, but also take trips to Raptors games, go paintballing, have organized dodgeball games, eat group dinners, and so on—similar to BIOME in its heyday.

The program has only expanded over the years. For the Fall 2014 semester, over 30 FLCs are offered in the Faculty of Arts & Sciences, covering a range of subjects from biology to philosophy. The testimonials students have for these groups are just as powerful as those for BIOME, and the numbers are even better. In another of Goldman’s year-end surveys, nearly every single student who participated in an FLC said they were glad they did, and that they made new friends.

And for Goldman, that’s really what he’s most proud of.

“People meeting people, students making new friends, and often more than casual acquaintances—students make best friends.”

Goldman is no stranger to this himself, by the way. He says one of his fondest memories is from a former biomer, who mentioned Goldman in his wedding speech.

“Years from now, students will forget many of the facts they learned in their classes. But hopefully, many of the friendships created through communities like BIOME and FLC will endure.”