Sian Meikle has also been involved in two other projects with the Provost’s Instructional Technology Fund, expanding and improving the framework for some useful existing websites.

Sian Meikle has also been involved in two other projects with the Provost’s Instructional Technology Fund, expanding and improving the framework for some useful existing websites.

The first, in 2006, was with the REED project—Records of Early English Drama. Their website, which Meikle originally helped build in 2003, contains a variety of information on the theatre troupes of Renaissance Britain, of Shakespeare’s heyday. Users can search for records of specific troupes, particular performance dates, the patrons of those performances, or even the different venues themselves. There are also detailed maps of Britain at the time, including an interactive one to explore the database with.

A few years after launch though, it became clear that the REED project’s basic database—the system with which it logged dates, names, venues, and so on—could be used for other performance records, from anywhere, or any time. So Meikle was brought on again.

With the ITCDF grant, she was able to re-work the website so its guts could be repurposed for other databases beyond REED, who didn’t have a way to put their information online before.

“Now,” Meikle says, “we’re letting lots of different scholars do their thing within that framework.”

So far three other websites are now supported by Meikle’s work, with the possibility for more.

Then, In 2011, Meikle used another ITIF grant to revitalize a classic University resource. The Representative Poetry Online site, or RPO, is the newest iteration of the high quality collection of poems that has existed since 1900. Professor Ian Lancashire originally put the poems online in the 1990s, as a series of text files.

“It’s one of the most heavily used resources for poems, all over the world,” Meikle says. “From high school students looking for assignments, to family members searching for poems to read at weddings or funerals.”

With Meikle’s help, however, the wealth of poetry and related information that Lancashire carefully compiled was streamlined, and given further life online. The website is easily updatable, with a host of interesting features.

Now, poems have clickable footnotes to explain references—if you ever wondered what the game of “pitch-and-toss” was while reading Rudyard Kipling’s If–, for example.

There is also an interactive map highlighting not only the death and birthplaces of famous poets, but the cities and landmarks around the globe that are mentioned in the poems themselves, like Phyllis Gotlieb’s description of Toronto’s Broadview Avenue in So Long It’s Been.

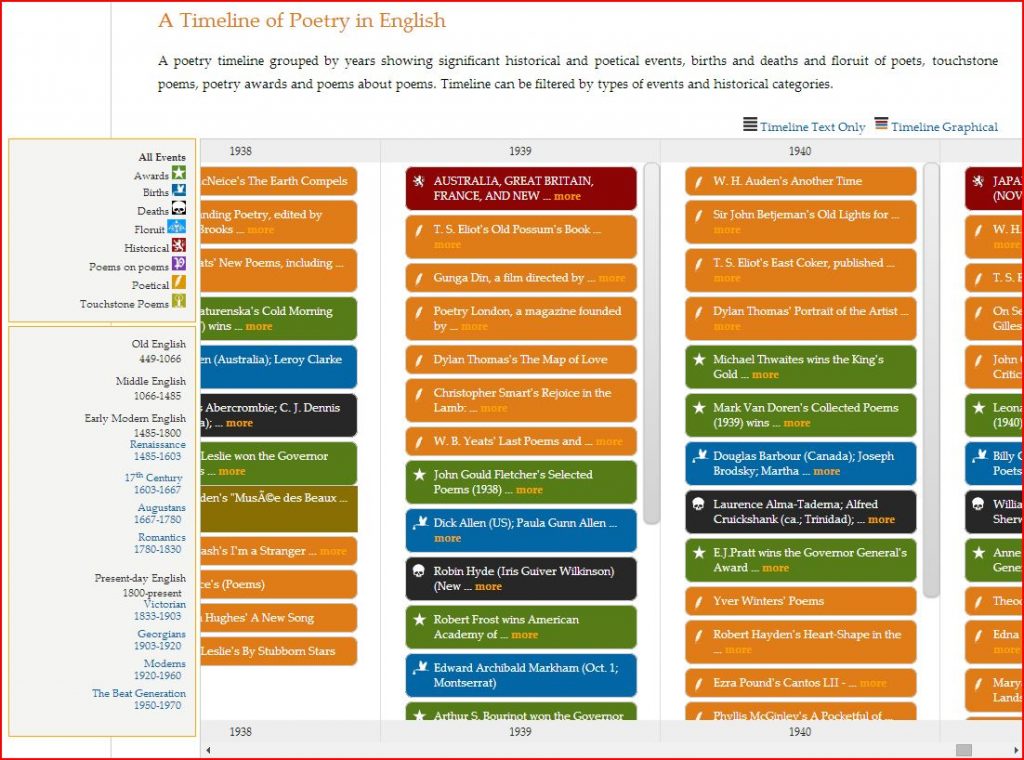

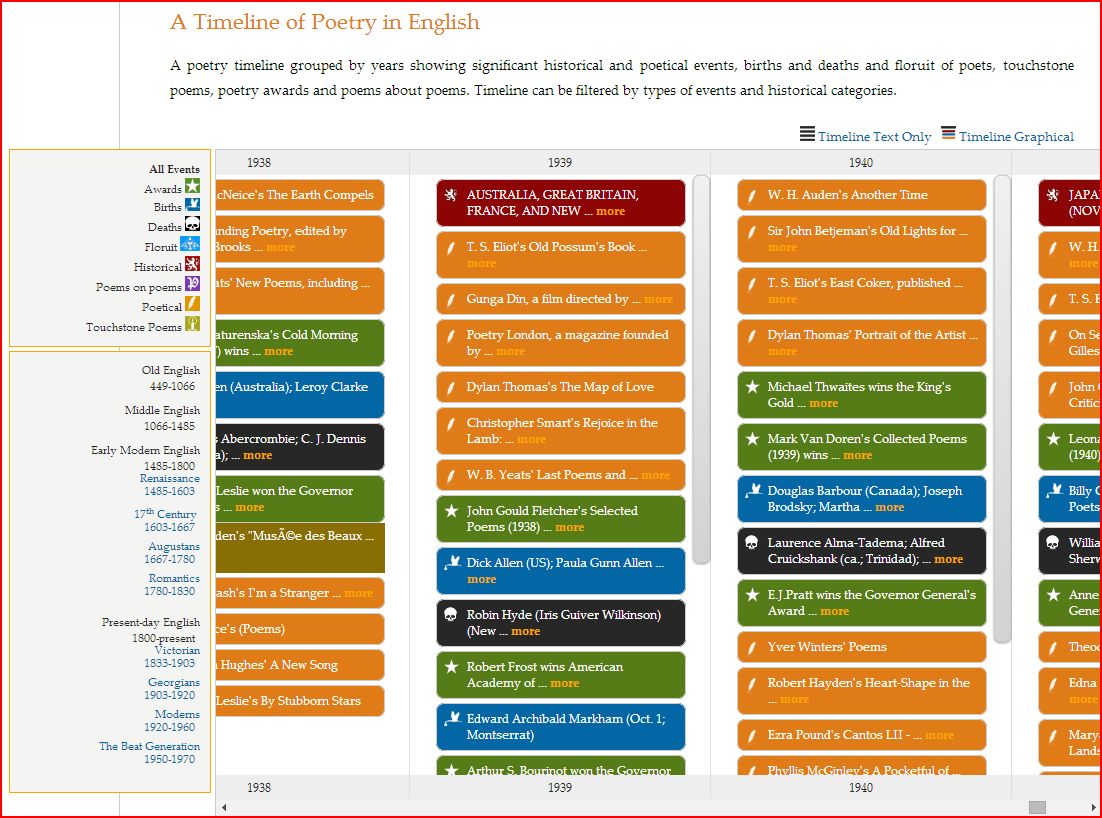

There’s even a series of timelines, stretching back to the year 449, which cover notable awards, historical events, births, deaths, and, naturally, poems. You can sort these timelines for things like “poems on poems,” (where one might come across Phoebe Carey’s I Remember, I Remember from 1854), or “poetical” (where you might learn that, in 2001, Professor John Basinger in Connecticut performed all 18 hours of John Milton’s Paradise Lost from memory).

And Meikle has more planned to improve the site in the future. She says that a feature allowing users to pull together customized lists of poetry is on the verge of coming out.

“It’s a really amazing resource.”